Secuencia de Inútiles

(Auto)retratos del yo. Miradas, memoria, historia.

13-17.09.2023

Artistas: Ben Vine (ing/esp), Delfina Lamas (arg), Ira Eduardovna (urb) y Mía de Diego (esp)

Todo aquel que interroga lo que le rodea no puede sino cuestionar su propia mirada. El retrato, esto es, el objetivar aquello que se mira no ha conocido otro reverso que el del autorretrato, es decir, la introspección a la que se ve sometido cualquiera que pregunta. De alguna manera, las obras reunidas en la edición de 2023 de PROYECTOR Festival de Imagen en Movimiento para la sede Secuencia de Inútiles orbitan en torno a la ficción, que no conoce otra cosa que no sea la autoficción; la representación, que siempre se autorretrata, y el yo, que ni siquiera cuando calla se desprende de su voz.

Una imagen rasgada, condenada a un anacronismo de colores pálidos y texturas rugosas muestra el que podría ser cualquier lugar: una calle en tránsito, una plaza interrumpida o una vía ocupada es el escenario que acoge la multitud de miradas y cuerpos que se topan con la cámara, ignorando su porvenir, interrumpiendo su trazado. Y, en el centro de la imagen, atrayendo su atención, una banda de músicos, impávida, resiliente. La videoinstalación de Ben Vine se concibe, al mismo tiempo, como un ejercicio de situación y como una proyección mimética. Velada (2005) supone un ensayo de exploración de la misma condición que lo vio nacer: la grabación, en una toma, con una super 8, de unos músicos en el mercadillo donde el artista consiguió la máquina fotográfica. Pero también se sustenta sobre la propia preocupación del que observa: la reflexión sobre los medios de exhibición y los lugares en los que se legitima la expresión artística. Aquellos músicos, al igual que la cinta que los filma, transitan entre el límite de lo aceptado y anulado, de lo reconocido y olvidado.

En la pieza de Delfina Lamas la textura granulada se ve sustituida por la tesela del píxel. En esta ocasión, es la cámara de Google Maps la que se desplaza por las calles de París. Con una voz muda, la artista recorre en primera persona los rincones, locales, esquinas y avenidas, así como los recuerdos que avivan cada una de sus instantáneas. Pero Un frente frío (2022) también sugiere aquellas otras imágenes perdidas en el tiempo efímero de lo digital. A medida que el recorrido se nutre de detalles y el espectador es capaz de recomponer el retrato en forma de paseo, se da rienda al recuerdo ensombrecido que explica el regreso a aquel lugar, pero también el que motivó su huida.

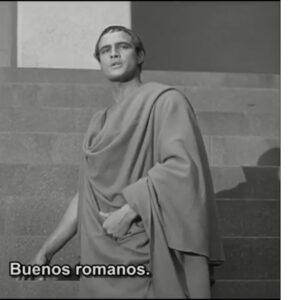

Por su parte, Mía de Diego reconstruye un retrato doble: el de Julio César y sus significados a lo largo de las décadas, y el de su padre, a quien observa y en quien se mira. A través de imágenes de archivo, documentales e históricas, Venividivinci (2020) hila una suerte de esbozo en torno a las equivalencias padre-autoridad, lenguaje-ley simbólica, víctima-verdugo. Bien sea a través de dos bestias al luchar, bien de dos niños que juegan, el retrato del padre se asoma desde una lejanía que sólo el consuelo de la expresión artística puede aliviar.

Por último, en la videoinstalación The iron road (2021), Ira Eduardovna rememora, en una reconstrucción de sus propios recuerdos a través de una doble pantalla, el viaje que trazó con su familia cuando migraron de Uzbekistán en los años 90. La artista recorre de nuevo el paisaje cambiante y trasfigurado que vio por última vez al huir de la antigua Unión Soviética. Algunos elementos se mantienen idénticos: maderas, apliques y ventanas en unos camarotes imperecederos que se deslizan por similares vías que atraviesan los mismos paisajes. Y, sin embargo, la posibilidad de encarnar el recuerdo mismo resulta irrealizable, pues, como todo fragmento de memoria, se torna resbaladizo, irrecuperable y, en último término, inconsistente con su propia verdad.

Texto: Luis Cemillán Casis

Anyone who questions what surrounds them can only question their own gaze. The portrait, that is, the objectification of what is looked at, has known no other reverse than that of the self-portrait, that is, the introspection to which anyone who asks is subjected. Somehow, the works gathered in the 2023 edition of PROYECTOR Festival of Moving Image for Secuencia de Inútiles venue orbit around fiction, which knows nothing other than selffiction; the representation, which always portrays itself, and the self, which even when it is silent does not come away from its voice.

A torn image, condemned to an anachronism of pale colors and rough textures, shows what could be any place: a street in transit, an interrupted square or a busy thoroughfare is the setting that welcomes the multitude of gazes and bodies that come across the camera, ignoring its future, interrupting its path. And, in the center of the image, drawing his attention, a band of musicians, undaunted, resilient. Ben Vine ‘s video installation is conceived, at the same time, as an exercise in situation and as a mimetic projection. Velada (2005) is an exploration test of the same condition that saw it born: the recording, in one take, with a super 8, of some musicians in the market where the artist got the camera. But it is also based on the concern of the observer: the reflection on the means of exhibition and the places where artistic expression is legitimized. Musicians, like the tape that films them, move between the limits of what is accepted and cancelled, of what is recognized and forgotten.

In Delfina Lamas‘ piece, the grainy texture is replaced by the pixel tile. On this occasion, it is the Google Maps camera that moves through the streets of Paris. With a mute voice, the artist goes through the corners, premises, corners and avenues in the first person, as well as the memories that enliven each of her snapshots. But Un frente frío (2022) also suggests those other images lost in the ephemeral time of the digital. As the route is nourished by details and the viewer is able to recompose the portrait in the form of a walk, the shadowed memory is given free rein that explains the return to that place, but also the one that motivated his escape.

On her side, Mía de Diego reconstructs a double portrait: that of Julio César and his meanings throughout the decades, and that of her father, whom she observes and who she looks at. Through archival, documentary and historical images, Venividivinci (2020) weaves a kind of sketch around the equivalences father-authority, language-symbolic law, victim-executioner. Whether through two beasts fighting or two children playing, the father’s portrait peers out from a distance that only the consolation of artistic expression can alleviate.

Finally, in the video installation The iron road (2021), Ira Eduardovna recalls, in a reconstruction of her own memories through a double screen, the journey she took with her family when they migrated from Uzbekistan in the 1990s. again the changing and transfigured landscape that he last saw when fleeing the former Soviet Union. Some elements remain identical: wood, sconces and windows in enduring cabins that slide along similar paths that cross the same landscapes. And yet, the possibility of incarnating the memory itself is unrealizable, since, like any fragment of memory, it becomes slippery, unrecoverable and, ultimately, inconsistent with its own truth.

Text: Luis Cemillán Casis